The ancestors of the AmerIndians that greeted the Spanish in the sixteenth century included Paleo Indians that migrated to California more than 20,000 years before present. Linguistic evidence, archeological evidence, and origin stories suggest that the people of the Americas followed three general paths. On the west coast of California, peoples arrived with the aid of small hide covered boats, while others walked coastal paths now under water due to climate warming, and still other groups waited until the ice corridor thawed to meander down the eastern side of the Rockies. In California four haplogroups are represented, all of which share commonalities with other Pacific Rim peoples. Of the three most dominant linguistic groups the oldest Penutian and Hokan arrived from the coast, while the third, and most recent, Uto-Aztecan originated from the Rockies to the east. When the Spanish arrived in California the population of indigenous peoples is estimated to have been 300,000. They spoke three hundred languages or dialects and lived primarily hunter gatherer lifestyles although some agriculture developed along the Colorado River. Loosely grouped there were eleven major tribal groups in the Inland Empire. Except for a couple of exceptions, the indigenous people of the area spoke Uto-Aztecan languages. From the first moments of contact with Europeans, native numbers declined. The coastal tribes faced the establishment of the missions after 1769 with some asistencias/estancias pushing inland, but the major inland contact began with American settlers. By the end of the nineteenth century, scholars estimate the population of the indigenous tribes had dropped to 16,000 people.

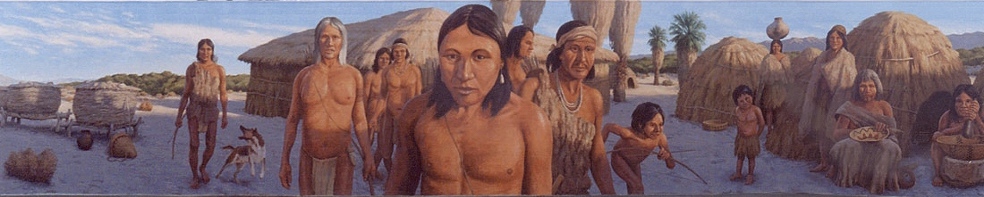

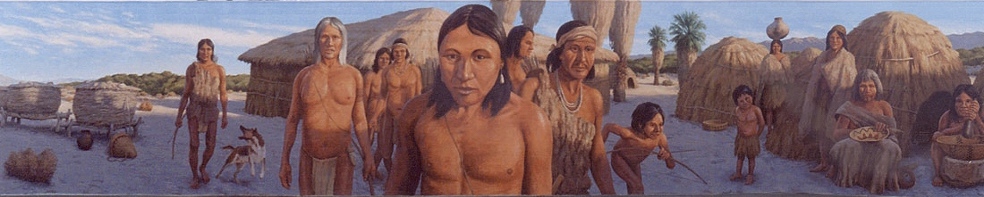

Header Photo: Cahuilla Village, By Don Gray, 1997, courtesy of Don Gray Studio

Since 1923, the long running play Ramona has been re-enacted in Hemet, California. The plot introduces a young Californio woman who falls in love with an indigenous man against her family’s wishes. They run away together and have a few happy years together until her husband is killed for horse theft. The melodramatic story was Helen Hunt Jackson’s (1830-1885) response to American Indian treatment in the nineteenth century. She grew up in Massachusetts but having lost her husband and two sons to illness and accident by 1870 she turned to activism and writing. One evening she heard Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca Indians tell of the plight of his people. Immediately, Jackson resolved to write a book to raise public awareness of the issue. Her first book A Century of Dishonor failed to attract an audience, so she decided to write a romantic novel reminiscent of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. That novel was Ramona, which was assumed to be a fictitious tale based on Hunt’s visit to Southern California in 1882 during which she visited Rancho Camulos, the future setting of her novel. The novel generated a fever for all things Californio and spawned its own tourist industry. But was the story true? Eventually, George Wharton James, a California promoter, discovered the “true” Ramona story. In 1883, while Jackson was in California, a Cahuilla Indian woman named Ramona Lubo (1853-1922) did lose her husband, Juan Diego, to violence when he “stole” Sam Temple’s horse in confusion. Temple followed Diego and killed him, in front of his wife and children. Sam Temple was acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense; Ramona could not testify because she was an Indian. Widowed, Ramona and her children moved to the Cahuilla Indian Reservation in Anza, California, where she wove beautiful baskets to sell at local Citrus Fairs.

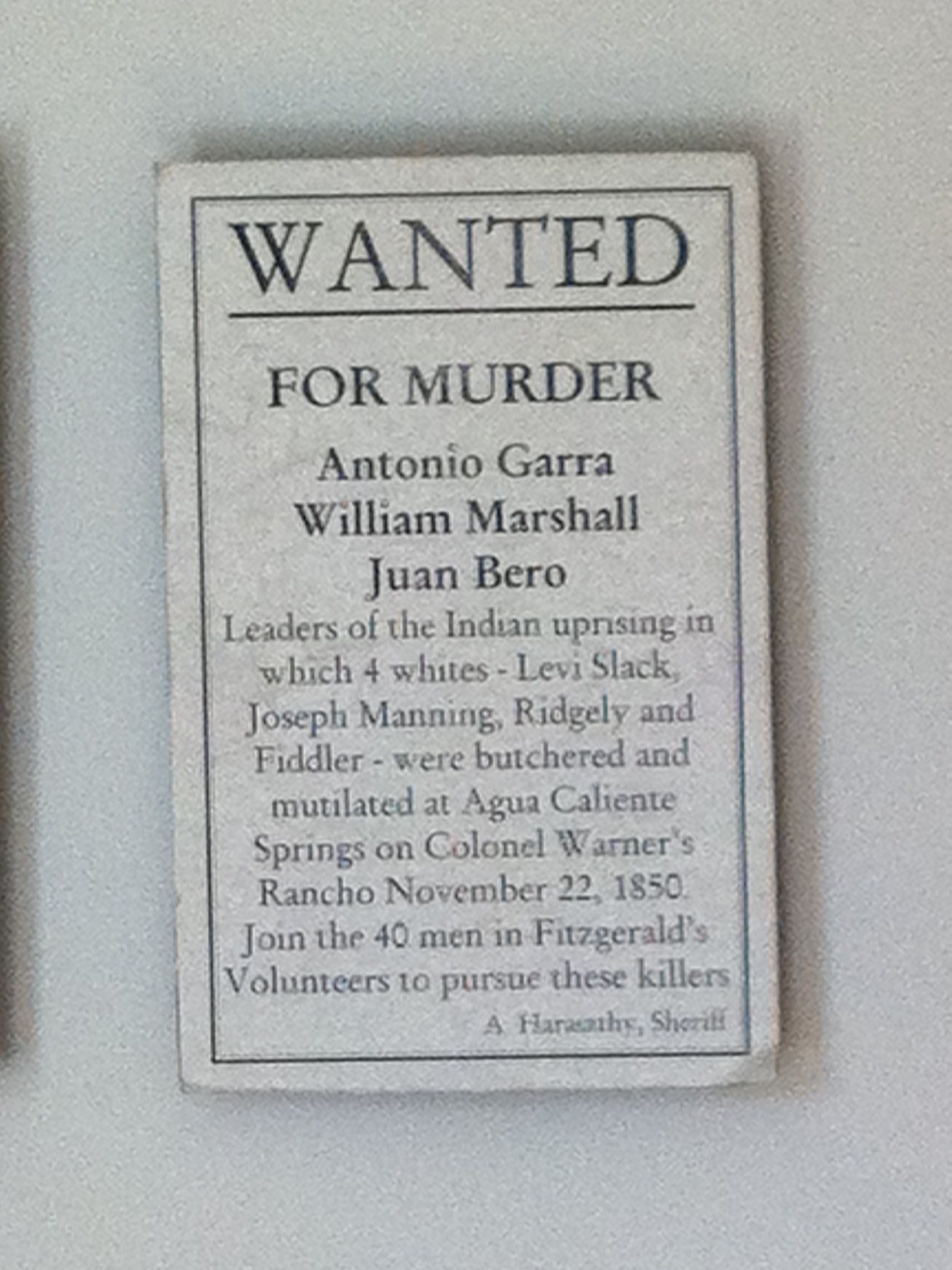

Life in 1851 California was complicated and dangerous! The Mormons built a fort to protect themselves from the Indians, the Californios hoped to retain power in California despite the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ceded California to the United States, and the indigenous tribes formed bands of warriors to defend their land under the direction of native chiefs, including Juan Antonio of the Cahuilla and Antonio Garra of the Cupeno. Some of the chiefs aligned with the Americans, some wished to oust all the foreigners, while others dreamed of a unified Indian future. In addition, self-interest parties encouraged the native attack, including, William Marshall and Juan Bero (see poster). Garra decided to unite the indigenous tribes and wrote to Juan Antonio, “If we lose this war, all will be lost.” The Anglos and Californios called in the army and fortified their towns and ranchos. Rumors said that Indians from Mexico north to San Bernardino were united in the effort. The attack on Warner Ranch in San Diego only proved the fears were real. Ultimately, the alliance between the Anglos and Juan Antonio proved strongest as he chose to throw his lot in with them and captured Antonio Garra. At trial, Garra was convicted and executed on January 17, 1852. However, as both a literate Catholic, fluent in three languages, including Latin, he had the last word: “I was advised…by Joaquin Ortega and Jose Antonio Estudillo, to take up arms against the Americans. They advised me …that if I could affect a juncture with the other Indian tribes of California and commence an attack upon all the Americans wherever we could find them that the Californios would join with us and help in driving the Americans from the country. They advised me to this course that I might revenge myself for the payment of taxes, which has been demanded of the Indian tribes…"

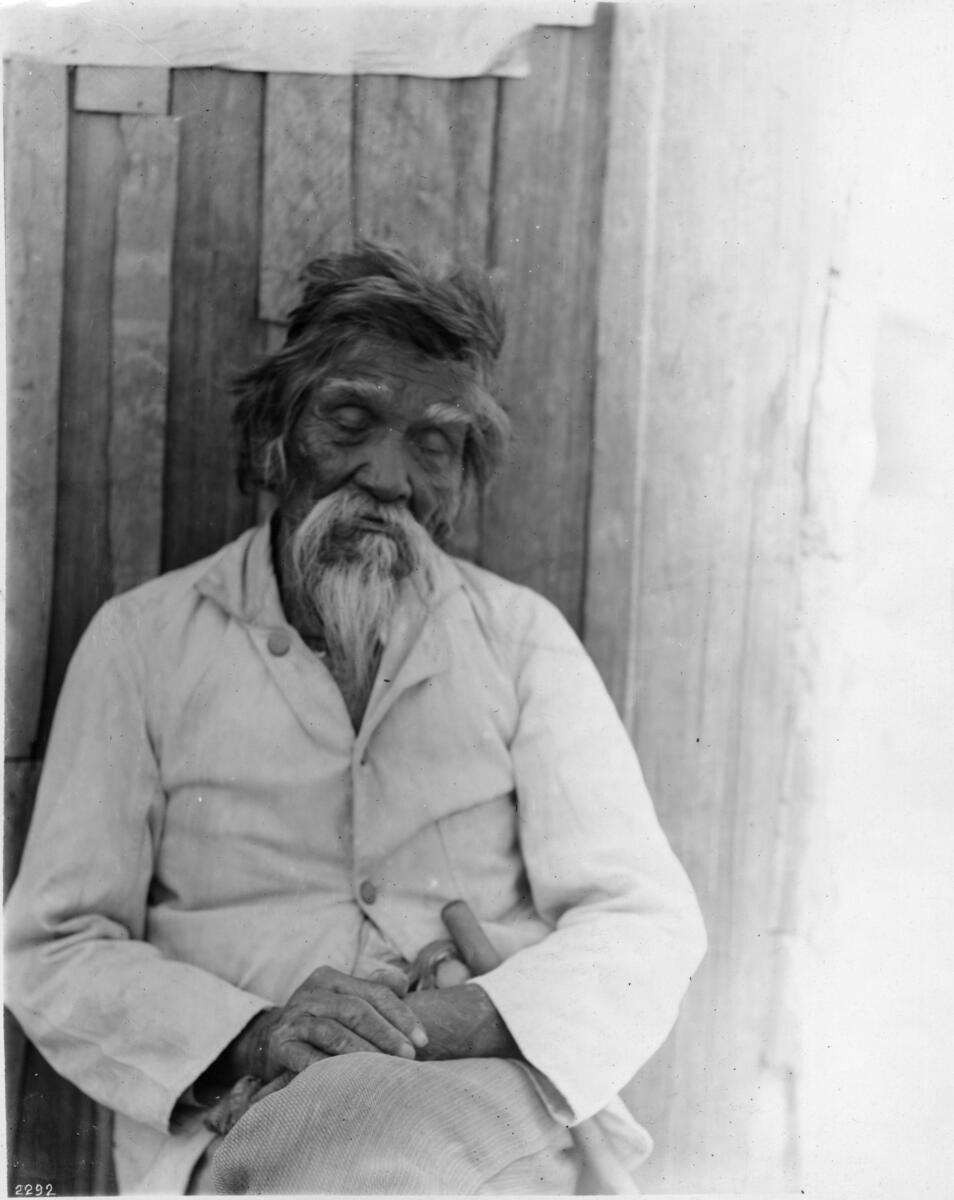

The story of Juan Antonio (1783-1863) stands out in California history because he was not a Mission Indian. Instead, he represents a native American with agency at a time when the opposite is often depicted. Antonio led five bands of Mountain Cahuilla for fifty years. He clearly understood legal authority and how to enforce it. In 1840 Juan Antonio took the offensive in stopping Ute horse thieves from entering his territory. Perhaps most intriguing was his protection of the rancho of Justice of the Peace Lugo. In 1810, Lugo’s rancho land belonged to Mission San Gabriel’s as an estancia. To protect his rancho, Lugo offered the area, called Politana, to Antonio’s tribe. From this position, Antonio acted as security for the rancho’s interests. In 1847 he avenged the Pauma Massacre in which a band of Luiseno Indians sough retaliated for horse theft by the Mexican lancers by killing them. In his role as security, Antonio killed the retaliating Indians in what is known as the Temecula Massacre. One might think his loyalty was to Lugo, but he also supported an American expedition led by Lt. Beale for which he was awarded epaulets that he wore into the grave. In summer of 1851, his warriors captured and killed the group of banditti known as the Irving Gang. On the way to Mexico the gang was

looting houses and threatening two of the Lugo sons. According to newspaper accounts from New York City Antonio’s force of attacking Indians numbered 300-400 men. Unfortunately, newly arrived Americans thought Antonio had no right to kill white men; they feared an uprising. Although a judge decided their actions reasonable, Antonio moved his band to Saahatpa in San Timoteo Canyon to avoid the Americans. Even when Chief Garra asked Antonio to join his revolt, Antonio refused and captured Garra instead. Antonio’s band of Cahuilla remained in Saahatpa until the smallpox outbreak in 1863 that wiped out the band and their chieftain.