Japanese immigration to the United States started comparatively late in the 1880’s. Initially, Japanese workers emigrated as workers to Hawaii, but by 1890, young men from Japan began to immigrate to the United States for job opportunities. Many found jobs in agriculture, as fisherman. or as day laborers. Those living in urban settings tended to group together in ethnic enclaves called “Little Tokyo.” Two other sets of Asian workers emigrated to the United States in the 19 th and early 20 th century. Chinese came to California for the Gold Rush and later to build the Central Pacific Railroad, while Filipinos came later for agricultural jobs on the West coast. Unlike China and the Philippines, Japan took a serious interest in its citizens working abroad. Japan was industrializing quickly. moving to subordinate Korea and China, and proving victorious in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. Japan also planned to dominate Pacific trade in direct competition with the United States. When San Francisco applied the Supreme Court case Plessy vs. Ferguson to segregated Japanese school students Japan objected strenuously, and Teddy Roosevelt intervened with “Gentleman’s Agreements.” In 1883 the Chinese Exclusion Act became law to slow Chinese immigration. Similar restrictive laws soon applied to other Asian groups, like the Webb Act which prohibited Japanese from owning property. By 1924 the Immigration Act effectively stopped most Asian immigration. As male immigrants established themselves in the United States they sent home for “picture brides” from Japan since miscegenation was illegal in the United States. By the time of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, 113.000 Japanese lived in the United States, two-thirds of them on the West coast. When the war broke out, the federal government viewed them as possible spies or collaborators. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Order 9066 in February 1942 ordering that all persons of Japanese ancestry in the Western Defense Command , whether they were citizens or not, move to relocation camps where most would remain until the end of the war.

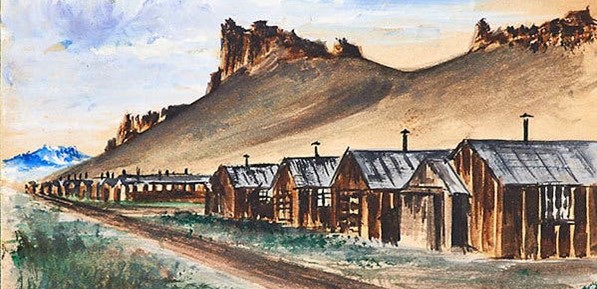

Header Photo: A watercolor by an unknown artist of a Japanese-American internment camp, from Rago Arts & Auction Center, via ArtNet

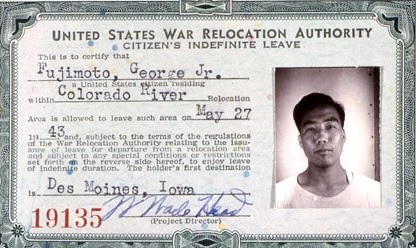

George Fujimoto (1921-2011) returned from college on March 11, 1942, at 5 pm to find that the FBI had arrested his father, who was an immigrant from Japan and a poultry farmer in Riverside, along with several other Japanese men. and taken them to jail under the direction of Executive Order 9066. George recorded the details in the diary he began shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and he would record his experiences and observation until after the war in 1948. By May 1942, George and his mother and five siblings (and spouses) were evacuated to the Poston Arizona Internment camp, just east of the Colorado River. The camp itself was comprised of three camps with a population of 17,000 at its height. It was so remote there was no need for guard towers. In July, his father was released from custody in New Mexico and allowed to return to his family. The following year his elder sister, her husband, and baby daughter received permission to move, called resettlement, to Des Moines, Iowa. When George found employment in a photography shop, he joined them until he was drafted to serve in the armed forces. His training was in the Military Intelligence School, specifically language school. After his training he deployed to occupied Japan until May 1946 as Sergeant Fujimoto. The internment camp at Poston closed in September 1945, since the war officially ended on September 2, 1945. His mother returned to Riverside then, and his father followed in June 1946. Before the government moved them to Poston, George rented the farm to a “white” family, and they were able to return to their property. By summer 1946, George returned from his service abroad, married and raised a family, and worked the farm until 1967. He later retired to Washington. The diaries from 1942 to 1948 are owned by the University of Riverside Special Collections.

In 1936, Kenge Kobayashi was born in Brawley, California, in the Imperial Valley. Brawley initially was a Japanese agricultural town, until the land was taken from the Japanese during World War II. The first Japanese settlers arrived in 1904 as farm laborers, and later many became farmers like Kobayashi’s parents. Unfortunately, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the fact that the farm was near a military installation made it a “red zone.” By January 1942 they were forced to sell their farm for $75. Before they were moved to the Gila River Internment camp in Fall 1942, they bunked with friends and then were moved to the Tulare Fairgrounds. Kobayashi remembered the visit to Gila River from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on April 23, 1943, when she expressed her opposition to the internment camps. If that was memorable for a positive reason, the 1943 loyalty questionnaires were the opposite. Historically, the main questions are numbers 27 and 28. Question 27 asked Nisei (second generation) men if they were willing to serve in combat duty and Question 28 asked if they could swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. His father and older brothers answered “no.” Those who answered “no” were termed “no-no” boys and were rejected by the “yes-yes” group and sent to the Tule Lake camp, a “segregation” camp. In Tule Lake, a group of Japanese were supporting Japan. One man was shot, and a riot ensued. Eventually, the men that were forcing Nisei to renounce their American citizenship were sent away and things calmed down. After the war, the Kobayashi family returned to Southern California to farm and Kobayashi was drafted into the Korean War. He then dedicated his life to his family and his career as an artist. Source: Oral History. Densho Digital Archive. July 4, 1998.

Originally published in 1946, Minè Okubo’s (1912-2001) autobiography of the Japanese internment camps called Citizen 13660 captures the history and the emotion of her World War II experience in the Topaz Internment camp in Utah. Her memoir differs from others as she was an artist whose book is a type of graphic novel. Like many internees her parents were emigres from Japan who arrived in the United States in1904 and worked hard to establish their home in Riverside, California. After high school, Minè’s artistic talent secured her a scholarship to the University of California at Berkeley. After graduating with her Masters, she left to study in Europe only months before Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. She caught the last ship out of France and retuned to the US to work on the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) until the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Executive Order 9066 became law in February 1942 and the government moved her family to a processing center and then to Topaz. On page139 of her book, she remarked, “A feeling of uncertainty hung over the camp; we were worried about the future. Plans were made and remade, as we tried to decide what to do. Some were ready to risk anything to get away. Others feared to leave the protection of the camp.” Luckily, in the camp of 10,000 people several were artists and together they organized an art school for the internees. In 1944, her artwork and drawings of the camp earned her “resettlement,” and early release program from the camps for “loyal” Japanese. She moved to New York City to illustrate for Fortune magazine. Soon after the war she published the first book on the internment of the Japanese. Minè continued to draw and paint throughout her life! In the 1980’s she testified to Congress about the removal of the Japanese in their move for reparations, which was passed in 1988.